Headed for the bottom: Yesterday, by happenstance, we experienced a rare mid-afternoon sighting.

By happenstance, we happened to watch this ten-minute, mid-afternoon segment on MSNBC. During the segment, Kate Snow interviewed two guests about our public schools.

Specifically, the segment was inspired by yesterday's Senate hearing involving Betsy DeVos, who will almost surely be our next secretary of education.

First, Snow interviewed a conservative who spoke in praise of DeVos. Then, she interviewed Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, who took a different view.

Largely because of her family's vast wealth, DeVos has played a major role in Michigan's public schools over the past twenty years. At one point, Weingarten issued a warning about the state of Michigan's schools in the age of DeVos:

WEINGARTEN (1/17/17): Look at the statistics from Michigan...What's happened in Michigan, on the same Naep test that you just talked about, they went from the middle of the pack in 2003 to the bottom, to 41 out of 50. That's not success. That's actually going backwards.We decided to check it out. To access state-by-state comparisons on the Naep, we skillfully clicked here.

Yikes! In terms of their rankings among the fiftry states, Michigan's school have been in a serious downward spiral during the age of DeVos. As always, we'll disaggregate.

Below, you see the relative standing of Michigan's white students in Grade 8 reading and math, as compared to their counterparts in the other 49 states. Some states didn't participate before 2003. For the sake of simplicity, we're omitting some intermediate testing years:

Michigan, standing among the fifty statesThat has the look of a terrible downward spiral. Here are the rankings for Michigan's black kids. Some states don't have enough black kids to produce a statistically significant sample for purposes of the Naep:

Grade 8 reading, white students, Naep

2002: 19 out of 41 states

2003: 12 of 50

2005: 30 of 50

[...]

2013: 41 of 50

2015: 42 of 50

Grade 8 math, white students, Naep

2000: 10 out of 39 states

2003: 25 of 50

2005: 31 of 50

[...]

2013: 42 of 50

2015: 42 of 50

Michigan, standing among the fifty statesAs compared with their peers in other states, Michigan's black kids started from a lower place than the state's white kids.

Grade 8 reading, black students, Naep

2002: 22 out of 32 states

2003: 29 of 40

2005: 33 of 39

[...]

2013: 33 of 42

2015: 39 of 43

Grade 8 math, black students, Naep

2000: 22 out of 28 states

2003: 35 of 40

2005: 32 of 40

[...]

2013: 41 of 43

2015: 37 of 39

Among the state's white kids, the drop during the age of DeVos is really quite extreme. As compared with their counterparts in the other states, both groups of students in Michigan now rank near the bottom.

You won't see these data elsewhere; the truth is, nobody cares. We'll also say this about yesterday's report on MSNBC:

Kate Snow is perfectly bright. She went to Cornell, then got a master's degree at Georgetown. Her father is an anthropology professor at Penn State. For some C-Span learnin', click here.

Snow brought nothing, zero, nada, to yesterday's discussion. She seemed to be reading perfunctory questions which had been prepared by staff. She showed no sign of knowing a thing about public schools or testing data, a topic she quickly introduced to no useful effect.

Snow looked great, and she's perfectly bright. But she seems to know nothing about these topics. Basically, she was phoning it in. Simply put, her owners don't care.

That said, the story is largely the same all through our liberal world. We'll pretend to squawk about DeVos. In truth, we don't really care.

Please note: We're talking here about relative standing among the fifty states. From 2003 to 2015, white students' average scores in Grade 8 math actually improved by a small amount in Michigan.

That said, average scores in other states improved a whole lot more. This left Michigan near the bottom in terms of relative standing.

In Michigan, black students' average scores actually dropped by a small amount during those same years. In the age of DeVos, with test scores rising, Michigan has been a major outlier.

Here's the good news for DeVos—nobody actually cares!

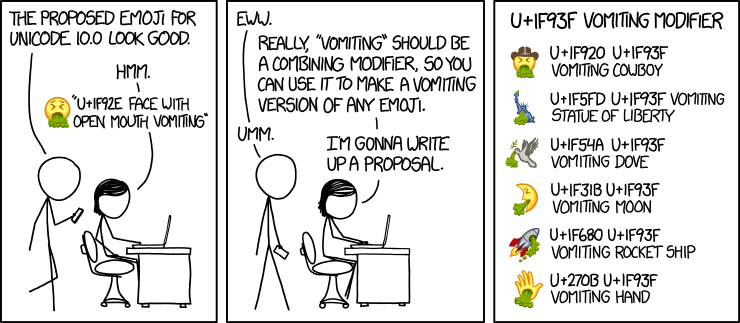

Hovertext: All other axiomatic systems shall be referred to as The Systems of Darkness.

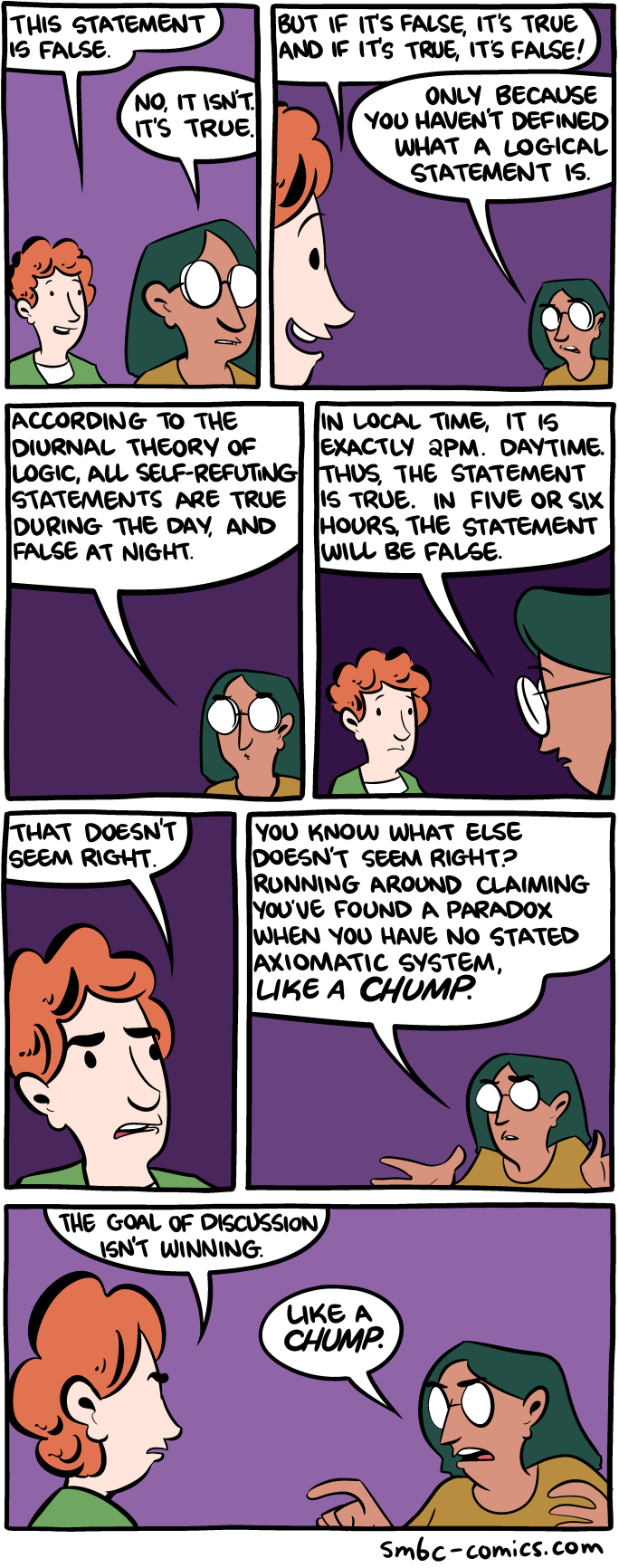

New comic!

Today's News:

A year ago, Harold Feld posted one of the most powerful ways of framing our excessive zeal for copyright that I have ever read. I was welling up even before he brought Aaron Swartz into the context.

Harold’s post is within a standard Jewish genre: the d’var Torah, an explanation of a point in the portion of the Torah being read that week. As is expected of the genre, he draws upon a long, self-reflective history of interpretation. I urge you to read it because of the light it sheds on our culture of copyright, but it’s also worth noticing the form of the discussion.

The content: In the Jewish tradition, Sodom’s sin wasn’t sexual but rather an excessive possessiveness leading to a fanatical unwillingness to share. Harold cites from a collection of traditional commentary, The Ethics of Our Fathers:

“There are four types of moral character. One who says: ‘what is mine is mine and what is yours is yours.’ This is an average person. Some say it is the Way of Sodom. The one who says: ‘what is mine is yours and what is yours is mine,’ is ignorant of the world. ‘What is mine is yours and what is yours is yours’ is the righteous. ‘What is mine is mine and what is yours is mine’ is the wicked.”

In a PowerPoint, it’d be a 2×2 chart. Harold’s point will be that the ‘what is mine is mine and what is yours is yours.’ of the average person becomes wicked when enforced without compassion or flexibility. Harold evokes the traditional Jewish examples of Sodom’s wickedness and compares them to what’s become our dominant “average” assumptions about how copyright ought to work.

I am purposefully not explaining any further. Read Harold’s piece.

The form: I find the space of explanation within which this d’var Torah — and most others that I’ve heard — operates to be fascinating. At the heart of Harold’s essay is a text accepted by believers as having been given by God, yet the explanation is accomplished by reference to a history of human interpretations that disagree with one another, with guidance by a set of values (e.g., sharing is good) that persevere in a community thanks to that community’s insistent adherence to its tradition. The result is that an agnostic atheist like me (I’m only pretty sure there is no God) can find truth and wisdom in the interpretation of a text I take as being ungrounded in a divine act.

But forget all that. Read Harold’s post, bubbelah.

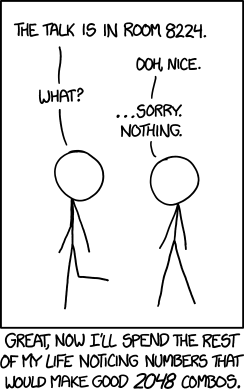

http://git.io/2048

Last Thursday, I took my son to meet Lucia McBath, because he is 13, about the age when a black boy begins to directly understand what his country thinks of him. His parents cannot save him. His parents cannot save both his person and his humanity. At 13, I learned that whole streets were prohibited to me, that ways of speaking, walking, and laughing made me a target. That is because within the relative peace of America, great violence—institutional, interpersonal, existential—marks the black experience. The progeny of the plundered were all around me in West Baltimore—were, in fact, me. No one was amused. If I were to carve out some peace myself, I could not be amused either. I think I lost some of myself out there, some of the softness that was rightfully mine, to a set of behavioral codes for addressing the block. I think these talks that we have with our sons—how to address the police, how not to be intimidating to white people, how to live among the singularly plundered—kill certain parts of them that are as wonderful as anything.

Jordan Davis was also given a series of talks, which McBath believes ultimately got him killed. We were sitting in the bar area of the Millennium Hotel in Times Square. She had a water. I had a coffee. My son sat back and watched. She talked about Jordan's first days in public school after several years of home school. She talked about how he went from shy caterpillar amazed at the size and scope of his new school to social butterfly down with kids in every crowd. He had strong opinions. She thought he would be a politician or an activist. It was in the blood. Her father, Lucien Holman, was head of the Illinois NAACP and served on the executive board. Lucia McBath herself is now the spokesperson for Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America.

"We always encouraged him to be strong. To speak out," McBath told me. "We tried to teach him to speak what you feel and think diplomatically."

She took a moment here. Her voice quavered but held. She said, "Even in that case with Jordan and the car, I think that he was not as diplomatic as he could be. That does not let Michael Dunn off the hook," McBath told me. "But I say to myself as a mother, 'I didn’t teach you and train you to do that. Adults are adults and you are still a child.'"

Agency is religion in black America. Benjamin Banneker made it. Harriet Tubman made it. Madame C.J. Walker made it. Charles Drew made it. Malcolm X made it. Barack Obama made it. You must make it too, and there is always a way. The religion of autoliberation is certainly not rebutted by the kind of graphs and stats that keep me up at night and that can easily lead to suicidal thoughts. Yours is the only self you will ever have. One must discover how to live in it or perish.

She continued, "In my mind I keep saying, 'Had he not spoke back, spoke up, would he still be here?' I don't know. But I do know that Jordan was Jordan to the end. I think Jordan was defending his friends. 'We’re not bothering you. We don’t know you. You don’t know us. Why can’t we play our music as loud as we want?'"

I told her that I was stunned by her grace after the verdict. I told her the verdict greatly angered me. I told her that the idea that someone on that jury thought it plausible there was a gun in the car baffled me. I told her it was appalling to consider the upshot of the verdict—had Michael Dunn simply stopped shooting and only fired the shots that killed Jordan Davis, he might be free today.

She said, "It baffles our mind too. Don’t think that we aren’t angry. Don’t think that I am not angry. Forgiving Michael Dunn doesn't negate what I’m feeling and my anger. And I am allowed to feel that way. But more than that I have a responsibility to God to walk the path He's laid. In spite of my anger, and my fear that we won’t get the verdict that we want, I am still called by the God I serve to walk this out."

I asked if she'd considered that Dunn might never be convicted of Davis's murder. "It's a strong possibility," she said. "The minute we looked at the jury instructions, we thought, 'That right there is what will keep Jordan from getting a guilty verdict.' I was crushed but not surprised."

A thought came to me that had been swirling for days: Dunn might win on appeal. I considered the possibility of him walking free. I considered the spectacle of George Zimmerman walking free. I considered the great mass of black youth that is regularly interrupted without any real reckoning, without any consideration of the machinery of black pariahdom. I asked McBath how she felt about her country.

She paused, then gave an answer that perfectly summed up the spirit of African-American patriotism. "I still love my country. It's the only country we have. This is the best that I've got," she said. "And I still believe that there are people here who believe in justness and fairness. And I still believe there are people here who don’t make judgments about people based on the color of skin. I am a product of that. But I am disheartened that as far as we've come it doesn't matter that we have a black president. It doesn't matter how educated we’ve become. It doesn’t matter because there still is an issue of race in this country. No, we have not really arrived. If something like this can happen, we have not arrived. And I ask myself, 'At what point are we going to get there?' And I have no answer. And I want to be able to answer."

She wanted you to know that Jordan Davis was an individual black person. That he was an upper-middle-class kid. That his ancestry was diverse. That he had blacks in his family. Mexicans in his family. Panamanians in his family. That his great-grandfather was white. That some of his ancestors had passed.

She wanted you to know that Jordan Davis was not from the "Gunshine State." That he was from Atlanta—Douglasville, Georgia, to be exact—where black people have things, and there is great pride in this. She wanted the world to know that Jordan Davis had things. That he lived in a three-story home in a cul-de-sac. That most of the children there had two parents. That original owners still lived in the development. That she was only the third owner. That Jordan Davis had access to all the other activities that every other kid in the neighborhood did, that he had not been deprived by divorce.

And she wanted you to know that Jordan Davis had a father. That this was why he was living in Jacksonville, where he was killed. That she was battling a second round of breast cancer and Davis's father said to her, "Let me raise him, you get well." She wanted you to know that she never ever kept Davis from his father. That she never put Jordan in the middle of the divorce, because she had already been there herself as a child—placed as a go-between between her mother and father. She said that this had wreaked havoc on her as a young woman. That it had even wreaked havoc on her own marriage. That she had carried that pain into relationships, into marriage, and did not want to do the same. She wanted you to know that Davis's father, Ron, is a good man.

She wanted you to know that what happened to Jordan in Jacksonville might not have happened in Atlanta, where black people enjoy some level of prestige and influence. That Jordan believed the level of consciousness in Jacksonville was not what it was in Atlanta, and that this ultimately played into why Jordan spoke up. That this ultimately played into why he was killed. I thought of Emmett Till, who was slaughtered for not comprehending the rules. For failing to distinguish Chicago, Illinois, from Money, Mississippi. For believing that there was one America, and it was his country.

She stood. It was time to go. I am not objective. I gave her a hug. I told her I wanted the world to see her, and to see Jordan. She said she thinks I want the world to see "him." She was nodding to my son. She added, "And him representing all of us." He was sitting there just as I have taught him—listening, not talking.

Now she addressed him, "You exist," she told him. "You matter. You have value. You have every right to wear your hoodie, to play your music as loud as you want. You have every right to be you. And no one should deter you from being you. You have to be you. And you can never be afraid of being you."

She gave my son a hug and then went upstairs to pack.